The Economics of Clean Energy

Zachary Bouck

Updated April 15, 2021 | Listen to the Mind of a Millionaire Podcast on iTunes, Spotify, or Stitcher.

March is a special month in that it marks the first day of spring—the joyous transition to longer days and warmer temperatures. I decided to veer from our routine financial tips and tricks in the spirit of the spring, instead exploring one of today’s more popular investment themes: clean energy.

As is true with any investment, an intelligent investor must have a diligent understanding of her holdings—something I’ve harped on time and time again. As Denver Wealth Management’s (DWM) chief investment officer, I am always intrigued to learn about trending investment opportunities—opportunities that I believe will best suit our clients.

Well, I read the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times, and I stay updated on Twitter, but I’ve noticed that clean energy headlines often skew investors’ perceptions. Thus, I wanted to learn more about the truth behind the surging investment craze and share my findings with you.

BREAKING DOWN INDUSTRY TERMS

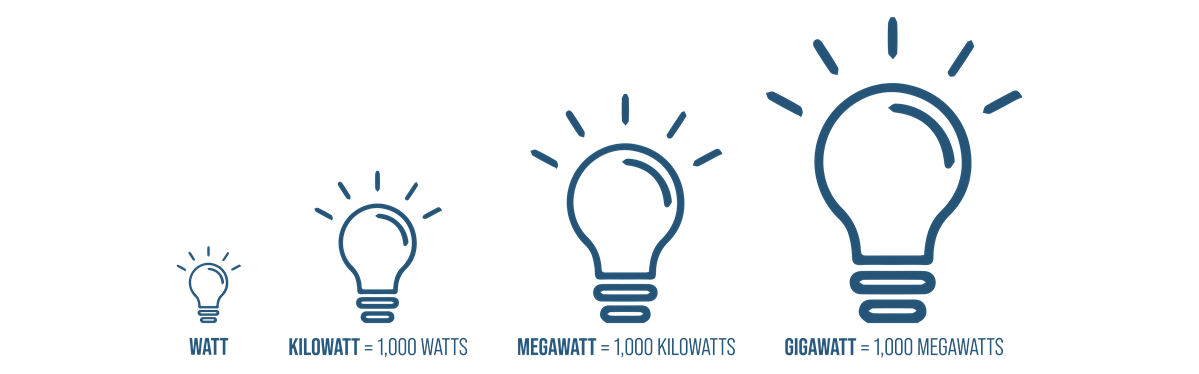

[2:22] First things first, let’s touch on the various terms used to describe energy. When you purchase a lightbulb, it’s measured in watts or watt-hours.

A watt is a watt. A watt-hour is simply a measurement unit of energy, describing the total amount of energy used over time. For example, if you have a 15-watt lightbulb, it draws 15 watts of energy at any one time and uses 15 watt-hours. If your lightbulb says “15 watt-hours,” then you know how much energy you would need to produce to turn on that light.

The next step up is a kilowatt. “Kilo” refers to one thousand, so one kilowatt equals one thousand watts. One kilowatt-hour refers to the use of energy at a rate of 1,000 watts. A kilowatt is generally used in reference to large appliances (e.g., refrigerators).

Next: the megawatt. One megawatt equals 1,000 kilowatts or 1,000,000 watts.

And finally, topping off the tower of power (clever, huh?) is the gigawatt. You probably caught on to the theme: one gigawatt equals 1,000 megawatts. Gigawatts generally refer to the capacity of large powerplants.

HOW MUCH ENERGY DO POWERPLANTS PRODUCE?

[3:48] As we explore clean energy, we need to consider how much electricity (energy) our nation’s powerplants produce, which brings up a fascinating trend. In the past ten years, the unsubsidized cost of new energy projects has completely altered in favor of wind, solar, and natural gas.

Historically, coal has been the dominant energy source across the United States—and globally—because of its low-cost nature. Fast-forward to the present day, even without government subsidies, industrial wind, solar, and gas are proving to be more profitable than coal plants. Clean energy is cheaper today than it was ten years ago.

THE NUMBERS

[5:51] Natural gas powerplants are currently the leading producer of energy in the United States. Although a large contributor to carbon emissions, when it comes to pollution, natural gas is considered relatively clean (compared to coal). Right now, there are 1,793 natural gas powerplants across the U.S., generating about 34% of the nation’s energy.

The second-largest generator of America’s energy comes from coal powerplants. With 400 plants nationwide, primarily located throughout the eastern U.S., coal powerplants generate 30% of the nation’s energy.

With 64% of our nation’s energy coming from natural gas and coal, there is a significant opportunity for clean energy to intercept a portion of that market. In other words, clean energy has a lot of room for growth, which can be exciting for investors.

Nuclear powerplants are the third largest contributor to our nation’s energy, providing roughly 20%. Although nuclear energy isn’t as widely discussed, it’s a substantial producer—some may even call it a power player.

Moving on from my witty energy-sector puns, hydroelectric plants produce 7% of our nation’s energy, largely because it’s easy to implement.

[8:02] Alright, on to the trendier methods of clean energy: wind and solar. Currently, there are 999 industrial wind powerplants across the U.S., generating 6% of our nation’s energy. Wind is the fastest-growing power source, which makes sense.

I grew up in Dickinson, North Dakota, where the weather forecast regularly consisted of two elements: the temperature and the wind speed. What was once simply an annoyance is being captured in larger capacities to create energy.

Last and pretty close to least is solar energy. Solar energy is growing rapidly in popularity—it seems as though more and more houses are blanketed with solar panels these days. However, rooftop solar panels are relatively inefficient on a larger scale, so note that I am describing industrial solar powerplants when I discuss solar energy.

With 1,721 solar powerplants nationwide, our sun contributes to about 1% of electricity in the U.S.

POTENTIAL PROFITABILITY IN CLEAN ENERGY

[9:55] Let’s get hypothetical for a minute. Let’s say you’ve accumulated $1 billion with which you would like to build a powerplant. You have four options: coal, natural gas, wind, and solar. For this hypothetical, we’ll assume no government subsidies are at play.

After you’ve built your plant, coal would cost $88 per megawatt-hour. Compare that to wind, which is the cheapest, at $36 per megawatt-hour (solar: $45; natural gas: $40). Coal is far more expensive; thus, investing in clean energy is no longer an ethical position reserved for environmentalists but a profit-seeking opportunity for capitalists. Harvesting green resources is becoming more economical than mining for coal. As a hypothetical energy plant owner, I would assume that you’d be inclined to produce a significantly cheaper product.

[12:51] To further drive the point home, let’s look at lithium-ion batteries—the batteries that power electric vehicles. In 2010, the volume-weighted average cost per kilowatt-hour stored in a lithium-ion battery was $1,191.

In 2020, it cost $137 to store the same kilowatt-hour of energy. I don’t know the science behind any of that measurement jargon, but the fact that the cost dropped by 90% is incredible from an investor’s perspective.

Electric cars are becoming far more economical than they were ten years ago.

THE CHERRY ON TOP & FINAL THOUGHTS

[14:08] If you look at the Covid-19 stimulus bills passed globally, $912 billion were earmarked for green energy—the European Union made up 72% of that; the U.S. just 2%.

That indicates a significant interest in green energy worldwide. The government, which has historically invested in the environment, has recently increased its contributions dramatically.

[15:25] This podcast and article has been an information dump, I know. But it all boils down to a few key points:

One: Clean energy, such as wind and solar, only makes up about 7% of our nation’s energy, leaving a considerable portion of the energy sector left to tap.

Two: As shown by the sharp price decline in the cost of lithium-ion megawatt-hours, clean energy sources are much cheaper to maintain than just ten years ago.

Three: Globally, the government is taking a much more active stance in green energy with loose fiscal policies.

Regardless of your attitude toward clean energy, the industry’s financial evolvement—and overall profitability—from just ten years ago may be something for all investors to consider. I had a blast learning about this, and I hope you learned a thing or two. If you found this interesting or have any thoughts, please let me know: zachary@denverwealthmanagement.com.

As always, call our office at (303) 261-8015 or schedule a free consultation to address your long-term financial goals.

For weekly market insights, join our email list.

Disclosures

Securities offered through LPL Financial, Member FINRA/SIPC. Investment advice offered through Denver Wealth Management, Inc., a registered investment advisor. Denver Wealth Management, Inc. is a separate entity from LPL Financial.

The opinions voiced in this material are for general information only and are not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual.

All investing includes risk including the possible loss of principal. No strategy assures success or protects against loss.

The economic forecasts set forth in this material may not develop as predicted and there can be no guarantee that strategies promoted will be successful.

All information is believed to be from reliable sources; however, Denver Wealth Management, Inc. and LPL Financial make no representation to its completeness or accuracy.